The oceans host organisms invisible to our eye among which some produce almost half of the oxygen we breathe. These organisms are capable of capturing light and CO2 to generate energy and O2 through a process called photosynthesis. The most abundant of them all are cyanobacteria that are prokaryotic ancestors of eukaryotic algae. Cyanobacteria comprise different species, but the two commonly found in the world oceans are Prochlorococcus and Synechococcus. They were discovered sometime around the late 1980s as a result of improved research technology that allowed scientists to look at the smaller components of our oceans. Although similar in that they have been around for millions of years, Prochlorococcus and Synechococcus differ in their photosynthetic assets.

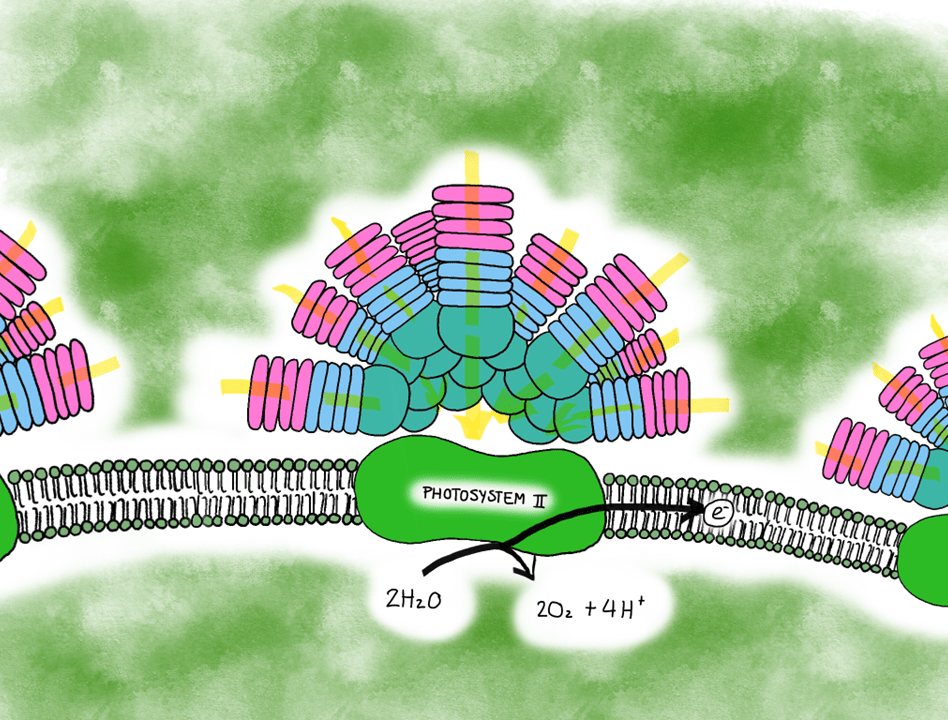

While Prochlorococcus posses a form of chlorophyll a called divinyl chlorophyll a and chlorophyll b, Synechococcus contain the common form of chlorophyll a and accessory pigments called phycobilisomes. These accessory pigments have three distinct phycobiliproteins: allophycoyanin, phycocyanin and phycoerythrin. Their purpose is to trap light energy – photons – and channel it to the photosystem II of chlorophyll a where the majority of photosynthetic processes occur.

Schematic representation of Synechococcus’s phycobilisome that consists of phycoerythrin (pink), phycocyanin (light blue) and allophycocyanin (turquoise) subunits. These channel light (yellow arrows) toward the photosystem II, which reacts with water to produce oxygen, hydrogen ions and electrons for the following light reactions. Illustration by: Aja Trebec

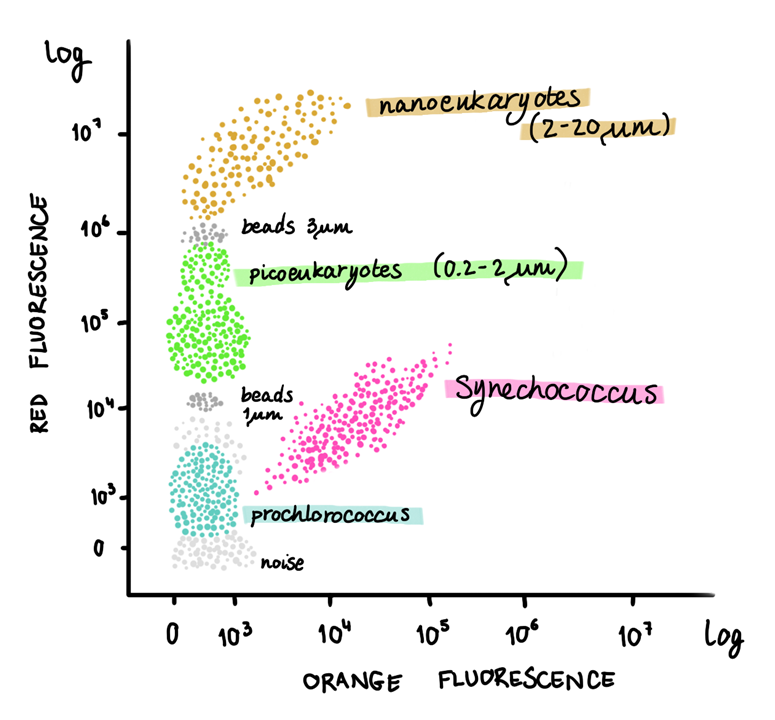

As Prochlorococcus and Synechococcus are similar in size, their photosynthetic traits can help us find whether a water mass has one, the other, or both cyanobacteria based on emission fluorescence of each pigment. Nowadays we estimate phytoplankton abundance and determine community composition with cytometric analysis, during which particles travel through the system and get excited by laser light of specific wavelengths. This analysis allows us to detect the emission fluorescence wavelength attributed to, for instance, chlorophyll a and phycoerythrin.

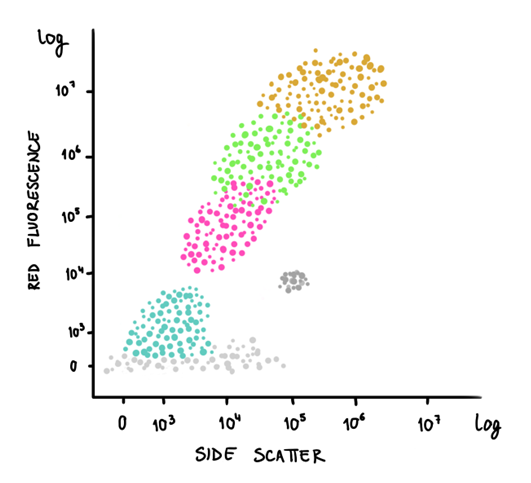

So when we observe a cloud of particles emitting a wavelength of 690 nm, they are releasing red fluorescence typical of chlorophyll a. On the other hand, when we observe a cloud of particles emitting a wavelength of 610 nm, they are releasing orange fluorescence typical of phycoerythrin. We are thus able to separate Prochlorococcus from Synechococcus, respectively. If we were to have more red fluorescence clouds of particles, however, we would have to look at cell size properties, such as the forward scatter (cell size) and side scatter (cell shape), which are essentially the “shadow” properties of the particles within a water sample. By doing so, we can detect bigger-sized cells like picoeukaryotes and nanoeukaryotes, bearing in mind they do not contain phycobilisomes like Synechococcus does.

Drawings of a cytogram (dot plot from flow cytometry) representing distinct marine phytoplankton populations based on the orange fluorescence (~ phycoerythrin) versus the red fluorescence (~ chlorophyll a) on the left, and side scatter (~ cellular complexity) and red fluorescence on the right. Illustration by: Aja Trebec

Thanks to cytometry and optical properties of organisms’ pigments, we can also extract information of the state of the environment, given other parameters (for example, photosynthetically active radiation, pH and inorganic nutrients) are provided. In the absence of growth, some phytoplankton may present enhanced fluorescence, hence indicating a change in their metabolic and photosynthetic functioning. This advance represents one of the many fascinating aspects of oceanography and remains to be explored as we seek for answers on how the world oceans work.

Aja Trebec

Written based on professional experience acquired before and during the doctoral thesis work.